Screeps #6: Verifiably refreshed

Assimilation (part 1): verification

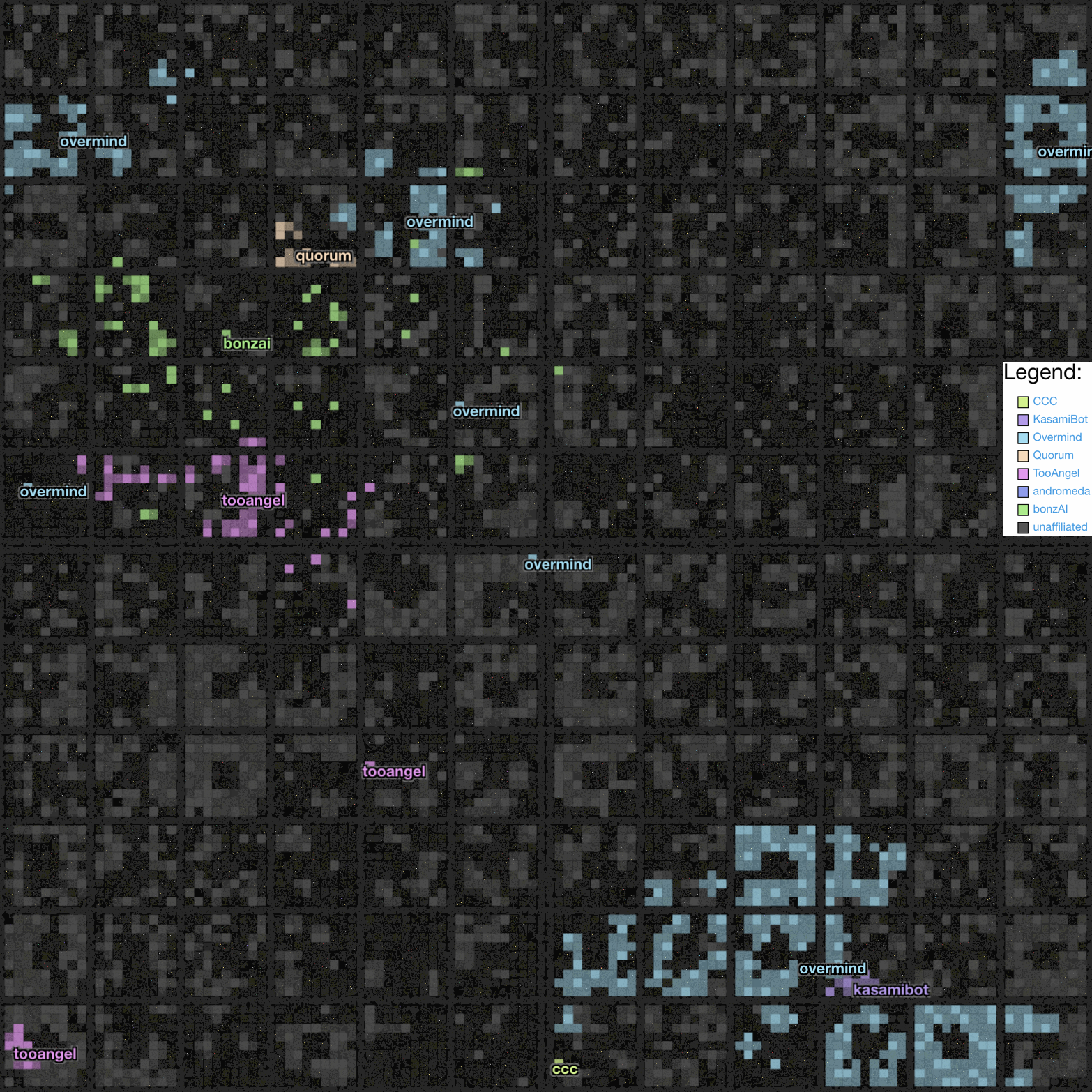

Over the last year, Overmind has gotten quite popular. It is now the dominant open-source bot running on the public servers, especially on shard2:

Having so many players running my script near me is a cool experience, and it gave me a thematically-fitting direction for Overmind’s final evolution: to become a true universal hivemind by assimilating other players.

Assimilation is a feature I’ve been teasing for a long time now. It allows all players running Overmind to act as a single, collective entity, sharing creeps and resources between each other and responding jointly to a master ledger of all directives shared by all players. When completed, (my) Overmind will truly be the overriding will of the Zerg swarm.

Before you get too excited, assimilation is still under construction and far from complete, but I decided to use a portion of this post to talk about an important aspect of it which has already been finished: verifying the codebase.

Because of how tightly integrated assimilated players will be, it is possible to modify the codebase to take advantage of the system. Since the codebase is open source, one could modify it to receive resources or combat assistance but never to give them when needed. Since I didn’t want to completely obfuscate the entire codebase, I needed a way to verify the integrity of certain parts of the codebase.

Enter the Assimilator.

The Assimilator is a global, persistent object which provides a way of deciding which Overmind players can be mutually trusted. There are a variety of ways it does this, some of which I won’t mention, but I’ll talk about the main verification method here.

If you’ve looked around my codebase recently, you’ve probably noticed some parts of the script which are marked with an @assimilationLocked decorator. This decorator registers that part of the code with the Assimilator, which ensures that it has not been tampered with. To do this, it exploits a wonderful (horrible?) behavior of Javascript, which is that if Foo is a class, then ''+Foo evaluates to a string containing the source code for Foo (!) :

class Foo {

constructor() {

this.bar = "baz";

}

}

console.log('' + Foo);

// > "class Foo {\n constructor()…z\";\n }\n\n}"

The Assimilator uses this behavior to generate a checksum of the @assimilationLocked portions of the script using a sha256 cryptographic hash. Whenever I deploy code to the main server, a checksum for my version of the code is generated and stored in my memory along with all unique hashes from the last 1 million ticks. If a player is assimilated, then every 1000 ticks, Overmind will send 100 energy to one of my terminals, with a hash of the current codebase as the description. If I receive a checksum which matches that of a recent valid version, I reply on the following tick with a unique clearance key valid for the next 1000 ticks transmitted through public memory:

The assimilator looks at the master ledger of clearance codes to determine which players are trusted. In the future, clearance keys will be used to generate flag names based on the tick they were created. Only flags matching the correct naming pattern will be uploaded to the master ledger of directives shared among the hivemind. This allows players to manually place their own directives which only their creeps will respond to (for fighting their own personal skirmishes), as well as for the Overmind to automatically place directives which all assimilants will see.

A refresh-ing new architecture

Prior to some recent changes, Overmind had never been a terribly CPU-efficient bot. A major reason for this is its very hierarchical, object-oriented architecture, which heavily employs classes. Classes are expensive to instantiate, and having many classes with shared references to each other and to game objects makes garbage collection in the V8 engine more expensive than for a flatter, prototype-based architecture.

To get a more detailed idea of why this was a problem, let’s look at Overmind’s main loop structure (which I talk about in more detail in a previous post). The important bits can be divided into three main (heh) phases:

-

build()Recursively instantiate all classes used by the AI. The Overmind object directly instantiates all colonies and directives, which instantiate their hive clusters, logistics networks, and overlords; overlords instantiate their Zerg (the wrapper class for creeps), and so on down the tree. -

init()Register all requests for actions to be taken this tick, such as creep spawning, requesting resources, or scheduling road repairs. -

run()All state-changing actions happen here: creeps are directed by their overlord, the Overseer adds and removes directives to respond to the environment, resources are distributed between colonies, trades are made with other players, and intel is gathered.

Some heavy profiling revealed that the build phase was using up almost as much CPU as the run phase (and if you include garbage collection time, possibly more)! Clearly this was not optimal…

The obvious solution was to make all of the classes persistent, but I had been holding off on doing this for two reasons: (1) much of Overmind’s codebase was written before isolated-VM, so this change would be a major undertaking, and (2) I was hoping that the devs would release persistent game objects, which they had teased back in August. However, after a few months waiting for persistent game objects while ignoring the growing elephant in the CPU-constrained room, I decided to just emulate their behavior myself. My solution was to use a set of new caching methods to add a new, alternate phase to the main loop: refresh().

In the new architecture, every n-th tick (where n=20 by default), the build phase is run, completely re-instantiating all script objects. On all other ticks, refresh() is run instead, updating all references to game objects while keeping existing script class instances alive, allowing for a “soft update” between ticks. The in-game properties are updated in-place by the $ caching module, which makes for easier garbage collection, and the wonderful generics type safety that TypeScript provides prevents me from doing anything stupid.

To get a more concrete idea of how this works, let’s look at an (abridged) example for how build() and refresh() work for a hatchery:

During the build phase, the constructor is called, overwriting the old hatchery object and re-defining properties for all of the structures. Particularly expensive calculations are done with the $.set() method, which takes a property name and a callback to compute a list of game objects; the callback results are cached to global and assigned to the specified property. During the refresh phase, these properties are updated in-place using the $.refresh() and $.refreshRoom() methods. In the global caching module, these methods look like this:

This new cache-friendly architecture has been running on the public servers for several months now, and is included in the new v0.5.1 release. After working a few of the kinks out, I’ve been very happy with its performance: the caching changes have reduced CPU cost by over 40%!

Brand advertising

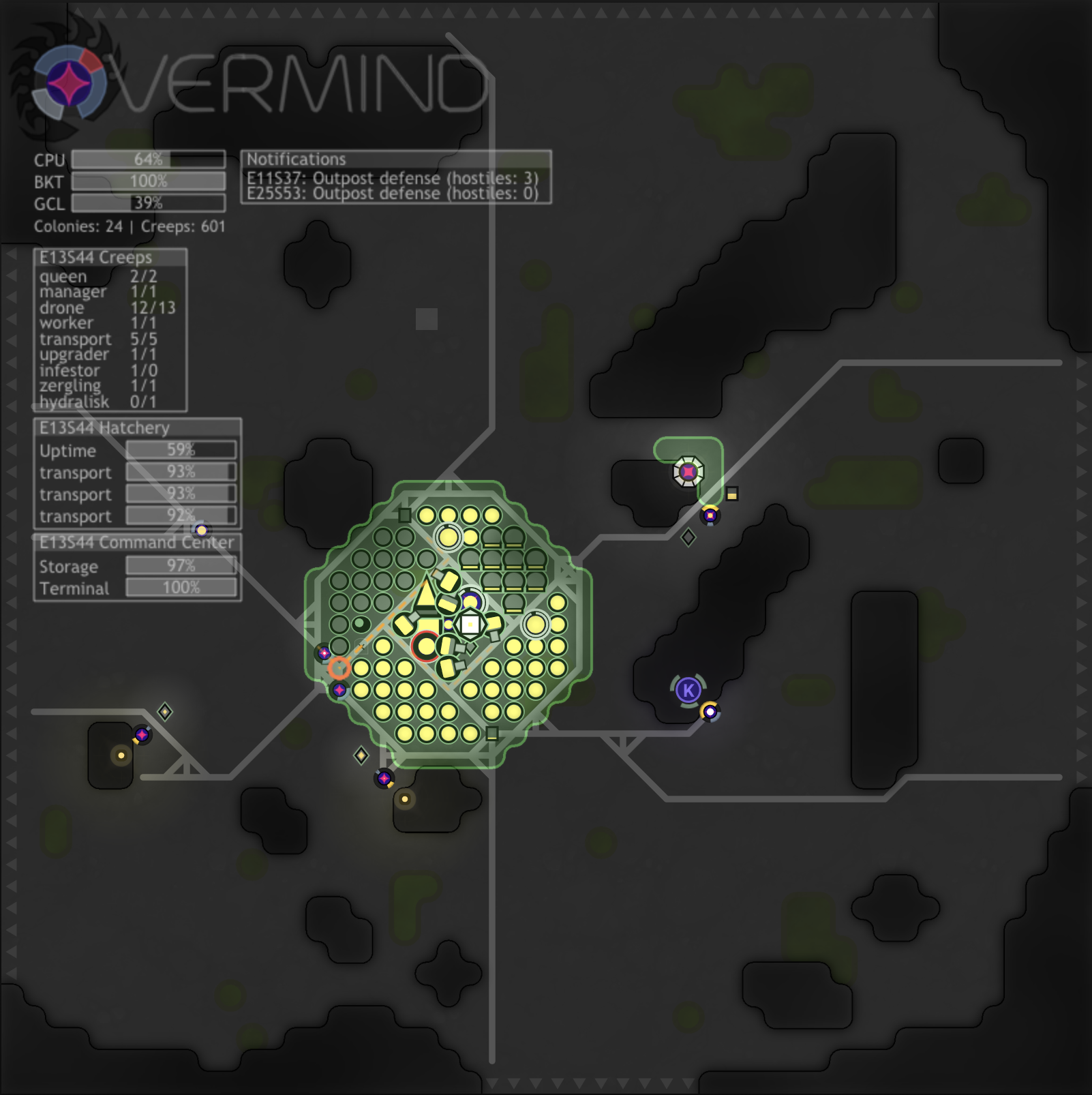

A while ago, I started rewriting the Visualizer system for Overmind to be better looking, better organized, and to display more useful information. Here’s a screenshot of what it looks like at the moment:

I generally enjoy writing visualization code, but the part I had the most fun making was efficiently rendering the Overmind logo using room visuals. If you’ve read any of my non-Screeps posts, you probably know that I really like Mathematica. I made a Mathematica notebook to disassemble the logo image into color-quantized components, and used the Ramer-Douglas-Peuker algorithm to parameterize the perimeter of each component into a form that RoomVisual.poly() can accept. This algorithm finds a minimum number of points necessary to outline a shape to within a specified tolerance. The (relatively) small point count means that the logo is actually quite cheap to render – about 1-2 CPU per tick. (And of course, visuals get disabled when the bucket drops below 9000.)

If you want to see how I did this, you can see the Mathematica notebook as a PDF or download the notebook source code here.