Screeps #4: Hauling is (NP-)hard

Logistics - the problem of efficiently transporting resources - is one of the most interesting and deepest problems in Screeps. (And it’s probably the single part of the game I’ve spent the most time thinking about.)

In this post, I’m going to talk about the overhauled logistics system I’ve spent the last few months working on. Since this post is really long (but I hope it’s worth the read!), I’ve divided it up into three parts:

- In Part 1, I’ll talk about the advantages and disadvantages of my old system and why it motivated an overhauled logistics system.

- In Part 2, I present a generalization of the “creep routing problem”, discuss why finding an exact solution is infeasible and motivate my approach in finding an approximate solution to the problem.

- Finally, in Part 3, I’ll give a detailed explanation of how my new logistics system works.

Part 1: Feeling “Boxed-in”

TransportRequestGroups (which existed in my old AI, but which I cleaned up in the Overlord Overload rewrite) act as a “box” to group prioritized resource requests. For example, each colony has a request group which suppliers attend to. At early levels, the hatchery puts requests into that group, but at RCL4+, the hatchery gets its own dedicated attendant (the queen) and its own request group.

This way of compartmentalizing requests proved to be quite useful in some cases, giving the convenience of “throw it all in a box” while still allowing me to specify which creeps do what. However, this system did not provide much in the way of flexibility. Isolating requests to separate boxes makes it difficult to handle more complex requests which need require multiple transportation “legs”, such as moving minerals to a terminal, sending them to another terminal, then transferring them from the terminal to a lab.

Greed is good… sometimes.

My old transport system took a greedy approach which was simple but inflexible, needlessly separating creep roles which could be combined. Haulers bring in energy from remote sources and put them in a dropoff structure and suppliers take energy from storage and distribute it throughout a room. (There are also 1mineralSuppliers1 and queens which have slightly-modified supplier logic.) This is basically how they worked in pseudocode:

function haulerLogic(hauler):

if hauler has a task:

execute the task

else:

if hauler has energy:

hauler.task = transfer energy to dropoff structure

else:

target = highest priority unhandled request

hauler.task = withdraw energy from target

function supplierLogic(supplier):

if supplier has a task:

execute the task

else:

if supplier has energy:

target = get closest high-priority unhandled request

supplier.task = transfer energy to target

else:

supplier.task = obtain energy from store structure

In the simplest case, the dropoff structure is only ever colony.storage, and this approach actually works decently well. However, things get hairy when you add multiple possible dropoff locations, such as when you build several dropoff links in a room.

Suppose you own a room that harvests from its left and right neighbors, so you put links on the left and right sides of the room, with the storage in the middle. A hauler could come in from the left, deposit to the left link, then start handling a request from the right room, walking past the storage and negating the usefulness of the link.

To solve this problem, I introduced the idea of miningGroups a while back. Mining groups bundle together mining sites by a common dropoff location, and each mining group has its own TransportRequestGroup and separate fleet of haulers. This prevents haulers from wasting precious CPU time wandering across rooms, but does cause problems of its own. Since it is CPU-efficient to always make the largest haulers possible to minimize per-tick fixed CPU cost, splitting a colony’s mining sites into several groups means that the expected hauler overhead (e.g. spawning 6 haulers when only 5.2 are needed) gets multiplied by the number of groups.

Additionally, this system is pretty inflexible. Haulers and suppliers have the exact same body layout, so they could be combined into one class, but the rigid rules-based structure of mining groups and request groups made it difficult to combine the roles. Having separate roles for resource influx and outflux also made it difficult to fulfill more dynamic requests, such as a worker who is fortifying a wall asking for an energy refill from a nearby hauler.

In redesigning my logistic system, I wanted to make a system with only one transport role which could flexibly and quickly respond to requests as they appeared. Making such a general-purpose system would require something more nuanced than a straightforward rules-based decision tree, so I spent a lot of time considering generalized versions of this problem.

Part 2: The Creep Routing Problem

(Disclaimer: this part contains a lot of math and isn’t really necessary to understand how the new logistics system works, so feel free to skip it and move to the next section if you get bored.)

The problem of optimally transporting resources around a room with a fleet of creeps is very similar to a well-studied NP-hard problem in combinatorial optimization called the vehicle routing problem (VRP), which is an extension of the famous traveling salesman problem. There are many variations of the VRP, but the most similar one to this problem is the vehicle routing problem with pickup and delivery (VRPPD), which seeks minimize a cost function for a fleet of vehicles which must visit pickup and dropoff locations. I’ll discuss a formalized version of the “creep routing problem” below, closely following the treatment of the VRPPD in [1].

Let \(G_{room}=(V_{room},E_{room})\) be an undirected graph representing the configuration of a Room, with vertices \(V_{room}\) corresponding to RoomPositions and edges \(E_{room}\) connecting any two adjacent RoomPositions which a creep can traverse.

Conceptually, a “request” is a resource that needs to be moved from one location to another, such as moving energy from a remote container into storage. Let \(R(t)=\{r_{i}\}\) be the set of requests at time \(t\), where each request is a tuple \(r_{i}=(o_{i},\{d_{j}\}_{i},q_{i})\) with origin \(o_{i}\), set of possible destinations \(\{d_{j}\}_{i}\) and capacity \(q_{i}\).

(This is a slight departure from the VRPPD: since all energy is the same, it can have multiple possible dropoff locations. For simplification, and to better adhere to [1], we denote all \(\{d_{j}\}\) as unique: that is, if a destination \(d_{1}=d_{2}\) is shared by two separate requests \(r_{1}\) and \(r_{2}\), we still treat \(d_{1},d_{2}\) as unique, such that a creep visiting this position can count as visiting \(d_{1},d_{2}\), or both. This is to simplify conditions 2 and 3, listed below.)

Denote the set of all origin nodes by \(O=\bigcup_{i}o_{i}\) and all destination nodes by \(D=\bigcup_{i,j}d_{ji}\). Let \(V=O\cup D\), and for each pair of distinct vertices \(v_{i}\neq v_{j}\in V\), let \(e_{ij}\) be an edge connecting them with weight \(w_{ij}\) (defined as the number of ticks it takes a hauler to travel from \(v_{i}\) to \(v_{j}\)). Let \(E=\bigcup_{i,j}e_{ij}\) and \(W=\bigcup_{i,j}w_{ij}\) and let \(G(t)=(V,E,W)\) be the complete undirected graph. Let \(C=\{c_{i}\}\) be the set of transporter creeps, where \(c_{i}=(p_{i},q_{i})\) with position \(p_{i}\in V_{room}\) and carry load \(q_{i}\le q_{max}\) for each creep.

A pickup and delivery route \(\mathcal{R}_{k}\) for creep \(c_{k}\) is a directed route through a subset \(V_{k}\subseteq V\subseteq V_{room}\) such that:

- \((\{o_{i}\}\cup\{d_{j}\}_{i})\cap V_{k}=\emptyset\) or \((\{o_{i}\}\cup\{d_{j}\}_{i})\cap V_{k}=\{o_{i}\}\cup\{d_{l}\}_{i}\) for all \(i,j\) and for at least one \(l\): creeps picking up from a request’s origin must drop off at one of the viable destinations

- If \(\{o_{i}\}\cup\{d_{j}\}_{i}\subseteq V_{k}\), then \(o_{i}\) is visited before any \(d_{i}\): creeps dropping off at a possible location \(d_{i}\) must have picked up their load from \(o_{i}\) first.

- \(c_{k}\) visits each location in \(V_{k}\) exactly once.

- The carried load is \(q_{k}\le q_{max}\) at all times.

A pickup and delivery plan is a set of routes \(\mathcal{P}=\{\mathcal{R}_{k}\}\) such that \(\{V_{k}\|k\}\) is a partition of \(V\). Let \(f(\mathcal{P})=\sum_{k}\sum_{j}\mathcal{R}_{k}w_{j,j-1}\) be the total cost of plan \(\mathcal{P}\) (defined in this case as the total amount of CPU it takes to execute the plan). Finally, the problem we want to solve is to find:

\[\displaystyle \min_{n}\{f(\mathcal{P}_{n})\},\]where \(\{\mathcal{P}_{n}\}\) is the set of all possible routing plans.

Definitely not NP-easy

Of course, even for small numbers of requests, this problem is intractable. At its core, finding an exact solution to this problem still boils down to solving multiple partitionings of the traveling salesman problem, which scales as \(\mathcal{O}(n^{2}2^{n})\) even using smart dynamic programming approaches.

Several papers have demonstrated clever exact solutions to VRPPD, such as [2], which used a branch-and-bound approach to find optimal routings for similar vehicle and requester numbers to what you could expect for a mid-size colony, but these typically took tens to hundreds of seconds to compute with a C++ implementation. (Certainly not friendly to your CPU bucket!) Clearly, an exact solution is not feasible. (And even if it was, the creep routing problem is a dynamic problem, so the solution could change every time a new request enters or exits the picture.) So, an approximate solution is needed!

An approximate solution

Finding an exact solution to the creep routing problem seeks to find a global minimum of CPU cost over all plans, so a decent place to start when looking for an approximate solution is finding a minimum of CPU cost for each individual creep over all “partial routing plans”: each creep does what will instantaneously maximize \(dq/dt\), where \(q\) is amount of resource transported and \(t\) is time in ticks. However, this basically boils down to the greedy approach unless we add some nuances to allow coordination between creeps.

A few months ago, I stumbled across a paper [3] which investigated the feasibility of dynamic taxi dispatching (think Uber or Lyft) with a stable marriage assignment algorithm.

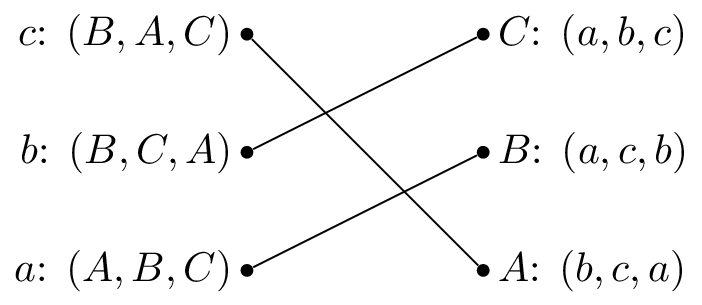

In case it’s been a while since your last algorithms class, the stable marriage problem seeks to find a “symmetrically greedy match”, or “stable match” (like the one shown above) between two groups based on preferences. To use the classic (albeit somewhat heteronormative) analogy, suppose you have a group of \(M\) men and a group of \(W\) women and that each person ranks the members of the opposite group by preference. A stable match is a one-to-one pairing of \(\min(M,W)\) men to women such that there is no man-woman pair who would both rather have each other than their current partner. Here’s a simple example of a stable matching:

It’s not too much of a stretch to replace “men” with “transporters” and “women” with “resource requests”, and stable matchings are easy to compute - Gale-Shapley runs in \(\mathcal{O}(n^{2})\) - so this approach got me excited. I started coding my logistics system based on this principle, but as always, the devil is in the details…

Part 3: The Logistics System

There are two entities in my new logistics system: requests and transporters. Request are submitted for targets that need a resource supplied or withdrawn (containers, towers, other creeps, even flags where resources are dropped), and transporters are resource-moving creeps. At its core, the new system works by trying to symmetrically maximize resource transport rate \(dq/dt\) for both transporters and requests: each transporter \(T\) ranks requests \(R_j\) they can respond to by \(\frac{dq}{dt}\|_{T,R_j}\), and each request \(R\) ranks transporters \(T_i\) that could respond to the request by \(\frac{dq}{dt}\|_{T_i,R}\). A stable matching is generated via Gale-Shapley to assign transporters to requesters.

Computing resource transport rate

As you might imagine, calculating \(\frac{dq}{dt}\|_{T_i,R_j}\) is a bit more involved than simply taking (change in resource) / (distance from transporter to request). When requesters submit a request with LogisticsGroup.request() or a withdrawal request with LogisticsGroup.provide(), several values are logged in a request object:

-

target: the object that needs resources in/out -

resourceType: the type of resource requested -

amount: the current amount of resources that need to be moved; positive for request() and negative for provide() -

dAmountdt: the approximate rate at which resources accumulate in the target (this is used to adjust the effective request amount based on the distance of each transporter) -

multiplier: an optional factor to multiply effective resources transported to prioritize certain requests -

id: a string identifier for the request; used for matching purposes

To calculate \(\frac{dq}{dt}\vert_{T_i,R_j}\), we need to consider multiple possibilities of what to visit on the way to fulfilling the request. For example, an empty transporter going directly to provide resources to an upgradeSite container would have \(dq/dt = 0\), but if it stopped by a “buffer structure” on the way, like storage or a link, it could have a large \(dq/dt\). So \(\frac{dq}{dt}\vert_{T_i,R_j}\) gets defined as the maximum resource change per total trip time over all possible buffer structures \(B_k\) that the transporter can visit on the way:

\[\frac{dq}{dt}\vert_{T_i,R_j}= \max_k \frac{\Delta q_k}{d_{T_i, B_k} + d_{B_k, R_j}},\]where \(\Delta q_k\) is the maximum of (resources/ or capacity in transporter, |request amount|, buffer resource or capacity) and \(B_0\) is defined to be the target, i.e. going directly there without stopping by a buffer on the way. If the transporter is matched to the target, its task is forked to visit the optimal buffer first. This logic is implemented in LogisticsGroup.bufferChoices().

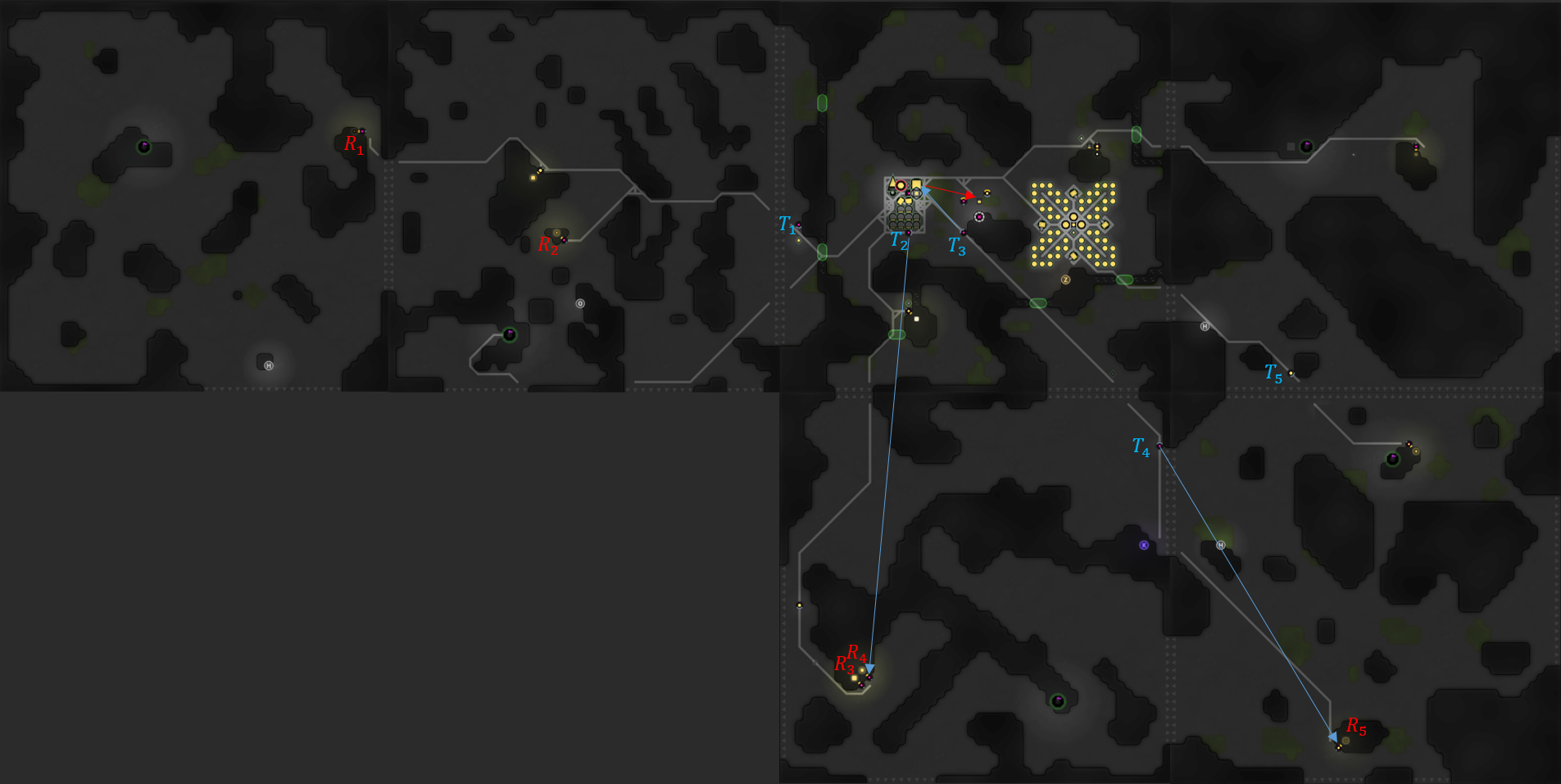

When calculating \(\Delta q_k\) and \(d_{T_i, B_k}\), the logistics system needs to compensate for what the transporter and other transporters are doing. To compute \(\Delta q_k\), predictedAmount() adjusts the effective amount for expected resource influx/outflux from the other transporters currently targeting the request target. (The state of the carry at the end of the transporter’s task is calculated with predictedCarry().) To compute the effective distance \(d_{T_i, B_k}\), nextAvailability() returns when a transporter will next be available and where it is expected to be. (My new task manifests were helpful here.) To better illustrate what these functions do, here is one of my colonies (click this for a higher resolution version):

Referencing the image above, even if \(R_1\) is nearly empty, predictedAmount(R1,T1) can be large because it is far away and there is nothing targeting it. However, predictedAmount(R5,T1) would be close to zero because \(T_4\) is targeting \(R_5\). If we wanted the next availability and carry state of \(T_3\) when it finishes what it’s doing, nextAvailability(T3) = [11,upgradingContainer.pos] and predictedCarry(T3) = {energy: 0}.

Putting it all together

Finally, as pseudocode, here is a stripped down version of my new transporter logic. This is shown only for the request() case - provide() is similar but slightly different - and predictedAmount(), predictedCarry(), nextAvailability() aren’t shown, but they do what they sound like. (See TransportOverlord.ts and LogisticsGroup.ts for the complete code.)

function transporterLogic(transporter):

if transporter has a task:

execute the task

else:

transporter.task = getTask(transporter)

function getTask(transporter):

assignment = LogisticsGroup.matching()[transporter]

function LogisticsGroup.matching():

tPrefs = {}

rPrefs = {}

for each transporter:

tPrefs[transport] = sort requests by dqdt(transport, request)

for each request:

rPrefs[request] = sort transporters by dqdt(transport, request)

matching = gale_shapley_matching(tPrefs, rPrefs)

return matching # keys: transporters, values: assigned requests

function dqdt(transporter, request):

# only shown for request() case, provide() is slightly different

amount = predictedAmount(transporter, request)

carry = predictedCarry(transporter)

[ticksUntilFree, newPos] = nextAvailability(transporter)

choices = [] # objects containing dq, dt, target

choices.append({

dq: min(amount, carry[resourceType]),

dt: ticksUntilFree + distance(newPos, request.target),

target: request.target

})

for each buffer:

choices.append({

dq: min(amount, transporter.carryCapacity,

buffer.store[resourceType]),

dt: ticksUntilFree + distance(newPos, buffer)

+ distance(buffer, requesttarget),

target: buffer

})

return (choice with best dq/dt)

I deployed this system to the public servers last week, and so far it’s been working really well. I seem to be using about 30% fewer creeps than my previous system used, and the total CPU impact is virtually unchanged (although it can be a little spikier on ticks where lots of colonies need to compute matchings at once). Overall, I’m really happy with how my new logistics system turned out!